The Iron Dream viewed from the Right

The longest review ever written on the book that taught lefties that every story they don't like is Sci-fi Biker Hitler.

I need to confess to something. I’m a sucker for a high concept. So The Iron Dream is perfect for me, at least in theory. The concept is both brilliant in its originality and elegant in its simplicity.

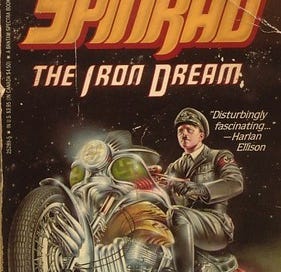

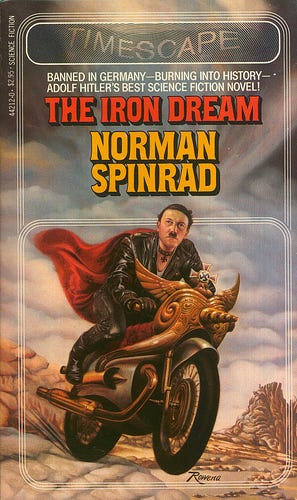

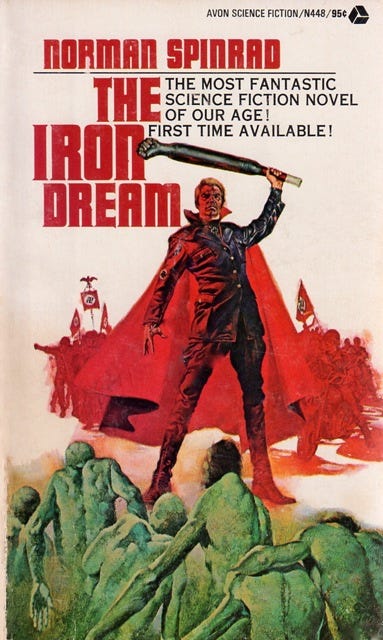

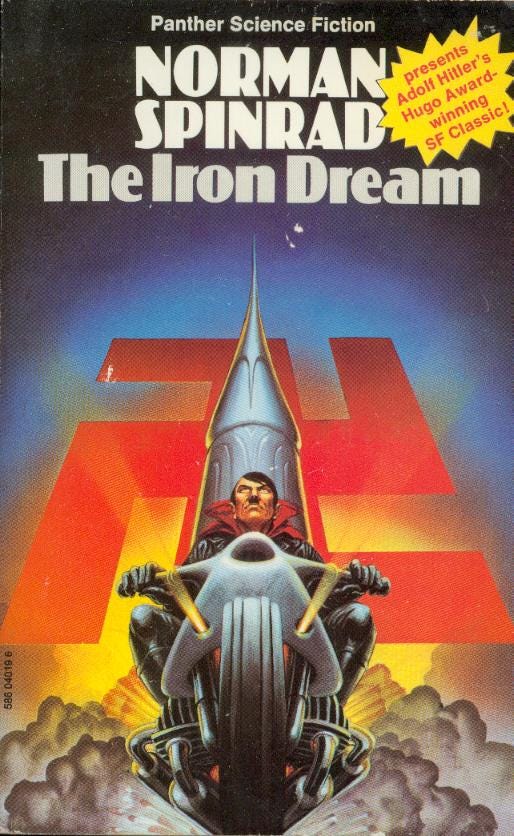

The premise of The Iron Dream is an alternate history where Adolf Hitler gave up on politics before ever becoming a notable figure and moved to America, where he became… a science fiction author. Most of the book is a novel within a novel. It’s Hitler’s last book, a pulp science-fantasy (a term used in the book itself, which actually arose as part of a socialist materialist movement to “purify” “real” sci-fi, which is a whole other can of worms) novel called “Lord of the Swastika.” This is couched between two framing devices that tell us about what sort of world this novel-within-a-novel was written in.

Spinrad and His Politics

Let’s get a couple things out of the way before diving into the content of The Iron Dream and the quality of the writing. Norman Spinrad is, or at least was when he wrote The Iron Dream, “that guy.” The one who says that evil races in fantasy represent minorities. The one who says that Goblin Slayer is a “Nazi show.” That guy. This was his main motivation for writing The Iron Dream. He thought that the pulp novels of his day were full of fascist and racist dogwhistles, and this was his way of critiquing them.

How many left wing pop-culture youtubers are regurgitating Spinrad, second or third hand, dumbed down to a modern 6th grade vocabulary and stripped of creativity? He wasn’t the first and certainly not the last, but he was possibly the first, and one of the few, to actually express this in a creative, artistic way instead of straightforward preaching.

Also, Norman Spinrad was a left wing anarcho-syndicalist. I’m using “was” to describe his views from now on, because as far as I know he hasn’t spoken about them lately, so I don’t know if they’ve shifted drastically, although considering some aspects of his 2007 book, Osama the Gun (particularly that when he wanted to make the main character dashing and sympathetic, Che Guevara apparently came to mind as a model) I suspect they haven’t.

For a lot of my readers, these things are probably throwing up some massive red flags. We’ve seen so much awful media pumped out lately by people whose politics at least superficially resemble Spinrads. But remember, The Iron Dream was written in a different era, and Norman Spinrad is OF a different era. A time when a syndicalist could actually tell you what syndicalism is and why he liked it without consulting his favorite breadtuber, because it was more than hip safe-edgy branding to him. A time when the traditional publishing industry still gave book deals at least somewhat based on merit (you didn’t have to write a good book, but it did need to sell, which sometimes meant just filling it with sexual degeneracy, but still overall a higher batting average than now). Plus I’ve already said that there have been works from the past made by people whose politics I vehemently disagree with that I’ve enjoyed.

So it had my interest. Let’s peel back the many layers of this narrative onion.

The Geek Culture Fuhrer

The first framing device for the book-within-a-book is a forward blurb containing a brief plot summary of Lord of the Swastika of the sort you’d see on the back cover of a book, followed by a list of other (fictional) works written by Hitler, and a brief (alternate) biography of toothbrush mustache man himself. Hitler moved to the USA in 1919, first got into the sci-fi community as an illustrator, then started writing and even published his own fanzine called “Storm.” He died shortly after completing Lord of the Swastika, which has long been out of print, despite winning a posthumous Hugo Award and being popular enough that the outfits from it are a fairly common sight at fan conventions. Now it’s finally being reprinted.

The “long out of print” line is a bit odd when you read the afterward, which is supposed to be an addition to this second edition of the book, and is dated 1959. “Lord of the Swastika” was supposedly published in 1953 and won a Hugo award in 1954. This doesn’t seem “long out of print” by my admittedly limited knowledge of tradpub, but whatever. Maybe it’s meant to be an in-universe marketing gimmick.

Lord of the Swastika

Now that the stage has been set without breaking kayfabe, the book-within-a-book, which is over 95% of the actual book, begins.

On the surface level, Lord of the Swastika is about a world after a nuclear apocalypse. The radioactive fallout mutated most humans and animals, leaving the mutants all physically deformed and mentally stunted to some degree, aside from the Dominators, who have human appearance, the ability to psychically influence people (within limits, their powers work better on mutants and the weak willed) and yearn to wipe out humanity for reasons that are never explained.

There’s only one country left in the world that’s controlled by truemen (unmutated humans), Heldon, which is also more technologically advanced than any other country. Protagonist Feric Jaggar is an exceptionally talented trueman born in a neighboring country that’s mainly populated by mutants, but who travels to Heldon planning to help fight to protect true humanity, which ends up involving taking the country over in a coup and waging total war on the Dominators and their empire of Zind. Also, he gets a giant magic club (although the “magic” is probably lost science) that belonged to the first king of Heldon, because every good pulp fantasy needs the hero to have a cool magic weapon.

Sounds pretty typical. The twist, of course, is that everything in Heldon is festooned with swastikas and other Nazi emblems, blond-haired, blue-eyed ubermensch Jaggar is hellbent on genocide of non-truemen from page one, and his rise to power in Heldon parallels the real-life Hitler’s rise to power in Germany (…sort of, we’ll get to that).

“Lord of the Swastika” is tough to critique, because pretty much any surface level criticism about the storytelling is usually deflected using the book’s meta nature as an excuse.

Feric Jagger, the protagonist, is cartoonishly one-dimensional.

“Well that’s the point.”

He’s also a Mary Sue, or whatever you want to call the male equivalent. He’s more capable than anyone else at pretty much everything, and there’s seldom justification for it.

“Well that’s the point.”

The story’s thematic elements are repeated excessively to the point of exhaustion. The clean vs dirty dichotomy of Heldon and truemen vs everything else. The overly long rally and parade scenes and repeating descriptions of black leather uniforms and swastika decorations. The genetic purity and race themes are inserted into practically every other paragraph in the first and final quarters of the book, never mind the long speeches about it. It makes reading extremely tedious after a while.

“Well, that’s the point!”

But is it, really? And if it is, is it a good point?

“It’s badly written on purpose.”

A very peculiar thing about The Iron Dream is that its biggest fans are, for the most part, also the most contemptuous of its actual content. Leftist and liberal fans of the book love to gush about how on point it is, while also saying that Lord of the Swastika (which is the vast majority of the book, remember) is horribly written (this Barnes and Noble staff writer called it “dreadful”). This is deliberate, they assert, because it’s imitating bad pulp novel schlock, and (according to some) also Hitler’s own limitations as a writer.

This sort of “review” of the book is suspicious because it happens to perfectly coincide with the political goals of the people sharing it. Lefties want to affirm Spinrad’s critiques, because critique is a form of cultural control (read section III of this behemoth of a piece if you want a full explanation why) and to validate that critique they also need to affirm Spinrad’s skills as a writer. If Spinrad is just some hack, people won’t take his criticisms seriously. At the same time, they can’t give the impression that they enjoyed literal pulp Nazism to any degree without at least two layers of protective irony. That would be a grave heresy to the progressive religion.

In fact, after reading many progressive reviews and commentaries on the book, I strongly suspect that a large portion of them didn’t actually read it, at least not all the way through. They probably did no more than skim it. Because in their reviews/blog posts/ etc, they’re just regurgitating the book’s afterward, with no new insights.

I’m going to do what few have bothered to do so far, and actually examine the content of Lord of the Swastika, not just the concept, both as text and with the subtext justifying it.

The first overlooked thing about Lord of the Swastika is that the writing is inconsistent. The first 30-40 pages of the book are much clunkier than the rest, from a prose standpoint. Jaggar’s internal monologues about genetic purity come hot and heavy, to the point where five pages in I was internally screaming, “Okay, we get it, thank you!” for the rest of this portion of the book. It’s why I dropped the book on my first attempt to read it.

And then… it lets up. The rest of the book isn’t nearly as bad in this regard. The book’s terminology also takes a hard shift. The word “genetic” and its variants are swapped for “racial” and Spinrad/Hitler never looks back.

The roughness of the beginning feels like a first time author finding his voice. But neither Spinrad nor alt-Hitler are first time authors. Spinrad had written two books before this, to moderate success. Per the book’s forward, alt-Hitler had already published eight novels by the time he got to this one. That wouldn’t necessarily make him a good writer, but it should make him a consistent one. Of course the afterward also suggests he was suffering from dementia from syphilis near the end of his writing, but that should effect the book’s ending more than its beginning. I don’t think the extra clunkiness early on is a deliberate choice.

While it’s not Spinrad’s first novel, and it’s not alt-Hitler’s first novel, it’s Spinrad’s first (and only) novel larping as Hitler. I think this is the real culprit. Growing pains in the persona Spinrad was adopting. Lord of the Swastika is never subtle in its message, but in the opening it’s downright preachy to the point of obnoxiousness. Ironically, it has the same issues that a lot of “woke” media has, as well as a lot of Christian/libertarian/right wing “moral alternative” media: message being emphasized over story. Except here the message is a sort of anti-message.

It ain’t all bad, actually.

When a biker gang boards his train, Feric challenges their leader, and is taken into a mystical forest to complete several trials, the painful repetition of the eugenics messaging almost entirely goes away. Maybe with the plot finally picking up, Spinrad allowed himself to forget about the “OMG Nazis” angle and focus on the pulp action adventure for a little bit. This segment is both the most reminiscent of something from a standard pulp adventure and the most enjoyable reading in Lord of the Swastika on an unironic, non-meta level. Even though the biker gang leader, Stag Stopa, is an expy of real Nazi Stormtrooper commander Ernst Röhm, their meeting and Stopa and his ganger’s recruitment doesn’t resemble how the real Röhm met Hitler or joined the Nazi Party at all. It’s very pulp, and if it weren’t for all the swastikas the biker gang is decked out in, one might completely forget that this isn’t a typical fantasy/sci-fi adventure. The trials are suitably tense and the forest is an interesting setting, with a lot of features and history mentioned that sadly never become important to the rest of the story. Even Feric being devoid of anything resembling likable traits doesn’t drag it down much.

Unfortunately, Feric and co eventually leave the forest, and start their political takeover of Heldon. I say unfortunately because this involves a whole lot of exhaustively detailed parades, motorcades, and rallies. Entirely too many detailed descriptions of swastika festooned cars and motorcycles, and endless lines of marching men in leather. The length of these rally scenes might not be entirely Spinrad’s fault. His publisher apparently ordered him to add an extra 10,000 words to the book after he finished it, so buyers would feel like they were “getting their money’s worth.” This was almost certainly for the worse.

There are still other aspects of Lord of the Swastika that are interesting and engaging in an unironic, non-meta way though.

The armies of Zind and the radiation jungles, although we sadly only get a small dose of both, are imaginative and evocative in a way a lot of modern genre fiction could learn a thing or two from. The radiation jungles are exactly what you’d expect from the name. Patches of jungle that are heavily irradiated and full of all kinds of wildly mutated plants and animals. Spinrad seems to have really had a field day coming up with morbid, bizarre descriptions for the animals. Featherless birds that leak acid and have floppy, prehensile beaks. Cows that trail their organs in sacks behind them. The plants, while less threatening, are no less bizarre. Stalks of grass as big as trees are mentioned at one point, and the plants mostly seem to be purple and blue.

It’s an alien landscape that’s just familiar enough to be easily and clearly visualized. Unfortunately the radiation jungles get very little page time, both because they’re largely unimportant to the plot, and the protagonists don’t have any protective gear so spending time in or near them is dangerous.

The Dominators of Zind are rather one-dimensional villains, but the way their armies consist of mutants who have been irradiated and selectively bred to be ideal for certain tasks while being (almost literally) mindless, makes for the most interesting battle scenes and delightfully grotesque visuals in the book. The common warriors of Zind are ten foot tall monstrosities with tiny heads. There are “puller” mutants (not actually named in the book) who are essentially just giant pairs of legs with overdeveloped thighs, stunted torsos, and even more stunted arms and heads. The Zind air force consists of giant slime birds(?) that drop sacks of acid. It helps that they’re the only enemy who ever actually poses any kind of threat to the Sons of the Swastika throughout the book. Everyone else gets curb stomped.

Lastly, Feric’s weapon, The Great Truncheon of Held is a bit of a vibe. It supposedly has the “mass of a mountain” (although this is probably an exaggeration, since a group of biker gangers are able to carry it around in a box, albeit not easily) but is genetically coded to be light as a feather for Feric. Everything it hits gets completely obliterated because it’s so dense and heavy. It’s an absurdly brutal weapon, while also being very simple and still having a major limitation (range).

In one of his many interviews about it (while still somewhat niche, The Iron Dream seems to have overshadowed the rest of his career) Spinrad described a letter his publisher had received by a man who thought the book was a fun adventure that had been ruined by all the “mucking about with Hitler.” Spinrad, like so many lefties tend to do, was expressing his consternation at this man “missing the point”, but honestly he might have been onto something. With a more likable protagonist, without the ham-handed eugenics message or the awkward attempts to mirror World War 2, with a focus on the interesting aspects of the world while letting the plot unfold in a more organic way, Lord of the Swastika would be a much more enjoyable story. Who knows, maybe if Spinrad had written a straightforward pulp sci-fi action adventure while indulging in his inner id he would’ve been some sort of George RR Martin equivalent instead of a niche author of stories with political subtext.

…Now I’m writing an alt-history of Norman Spinrad. We’re reaching meta-levels previously thought impossible.

The Author’s Meta-Lecture

The afterward of the book is another in-universe device, supposedly the actual afterward of Lord of the Swastika, written by a fictional academic named Homer Whipple, analyzing alt-Hitler’s writing and the fandom that has grown up around it. Homer Whipple is a mouthpiece for Norman Spinrad. The afterward is Spinrad telling the audience exactly what he was thinking when he wrote the book and what the message is supposed to be, albeit with some winking and use of irony. As I said before, a lot of the people who write “reviews” or “analysis” of the Iron Dream are really just regurgitating ideas from the afterward.

Spinrad lays the groundwork for “it’s badly written on purpose” here, with his character Whipple heaping a fair amount of shade on the writing quality of Lord of the Swastika, as well as what a bunch of tasteless troglodytes (not exact words) its fans are. It gets to the point where it actually damages suspension of disbelief about the framing device. Why is Whipple insulting a book and its fans in the afterward to the second printing of that book? Why would the publishing company print something so alienating to their customers? This sort of thing may have come somewhat into vogue with the rise of ESG scores, where companies can get paid millions by megawealthy financiers to tell their customers to “be better” and treating entertainment more like foul tasting medicine to be shoved down people’s throats, but I don’t think it was a thing publishers generally did in the 50’s and 60’s. Certainly I haven’t seen any prominent examples of this from the time.

Most of Whipple’s criticisms of the book’s writing quality are vague, and when he gets specific, his complaints don’t match the complaints I made earlier. He says that German terminology creeps into alt-Hitler’s prose. This does happen a couple of times, but the overall effect on the reading was negligible. He also mentions that alt-Hitler’s writing isn’t as good as Joseph Conrad’s. Joseph Conrad is widely considered to be one of the greatest English language writers of all time, so this comparison feels like it’s really stretching for something to bash alt-Hitler’s writing.

This is another major reason I don’t think the writing’s biggest problems are deliberate. The things Whipple/Spinrad cites as major problems are at most minor problems and the major problems aren’t mentioned at all. It’s like he knew it was clunky, but he seems to have missed the mark on WHY. Ursula K. LeGuin wrote a review of the book way back in 1973 that was one of the few to really dig into it beyond parroting Spinrad’s own claims, and she noted that, “There are obvious parodic elements in the style, which is prudish, slightly stiff, and full of locutions such as ‘naught but’; but in fact the style is seldom very much worse than Spinrad's own, before Hitlerization.” (Emphasis mine)

But enough beating that dead horse. Let’s get on to one of the biggest (and funniest) insights into Lord of the Swastika shared by Whipple: that the whole story is actually about penises.

Freud on Pervitin

Sigmund Freud has fallen out of favor nowadays. His “scientific” claims about psychoanalysis, the subconscious, and sexuality are widely considered to be discredited. But the man was considered to be THE great luminary social scientist for well over half a century.

And the older left-wing “media literacy” crowd fell for his ideas hard. In fact, they simplified and exaggerated his ideas. Even Freud himself said that sometimes a cigar is just a cigar, but in the eyes of many left liberal media critics for seven plus decades, a sword was always actually a penis.

The above screed is by science fiction writer and publisher Sam Lundwall. There’s a high chance you’ve never heard of him, but in the world of traditional genre publishing, he has actually been a formidable gatekeeper and highly influential figure. For more information on Lundwall’s influence, I highly recommend JD Cowan’s The Last Fanatics: How the Genre Wars Killed Wonder, which outlines Lundwall and his associates’ political crusade to shape science fiction in their own image.

Here’s my own response to Lundwall’s Freudian pseudo-intellectual absurdity:

Humans (especially human men) have been killing each other for about as long as humans have been having sex. The ones who were good at it survived and reproduced. Therefore it stands to reason that mankind’s attraction to and fascination with violence comes from man’s evolutionary history of… violence. Not sex. This attempt to paint an interest in violence as some sort of aberration arising from abnormal sexual development may be appealing to lefties of a pacifist bent, but like so many counterintuitive leftist theories it’s about avoiding the truth rather than shedding light on it. There’s absolutely nothing substantiating it, much like all of Freud’s theories, which is why they’ve all finally been swept into the bin.

So the Freudian screeds of the likes of Lundwall and Spinrad become less of an analysis their targets and more of an unintentional mirror, shedding light on the people making these assertions.

Spinrad seems to have hailed from the same school of thought as Lundwall, if he wasn’t an outright disciple of the man. He repeats all the same points from Lundwall’s excerpt above in The Iron Dream’s afterward. He notes all the phallic imagery in Lord of the Swastika, some of which he made deliberately exaggerated, most notably the story’s signature melee weapons, the truncheons, which are one of the more aesthetically unusual things in the story.

For those who don’t know, truncheon is a type of club. The real ones were quite short, intended for very close quarters fighting. The ones in Lord of the Swastika are described as being much longer. One is described as being a yard long, and the Great Truncheon of Held is four feet long (which makes the times when Feric sticks it in his belt kind of absurd, how does he walk?), making them more like a Japanese tetsubo or kanabo, except not studded.

The Swastika truncheons are also all described as having ornamental “heads” at the top. Stag Stopa’s is a skull, the Great Truncheon’s is a fist, and another one that briefly makes an appearance before getting broken has a head that looks like an eyeball.

Yeah, Spinrad found a sneaky way to arm everyone in Lord of the Swastika with what are essentially giant weaponized dildos. Any youtube weapons channels care to test out the practicality of The Iron Dream’s Truncheons? It would unironically be interesting and entertaining. Someone send this to Shadiversity!

But what’s the significance? At the end of the day, it’s still a melee weapon. It hits things and those things die. The same could be said about all the other supposed phallic symbols in the book. Some are obvious (a tower, a rocket ship) and some feel like Spinrad was really reaching when they’re mentioned in the afterward (heel clicking?). But why does any of it matter? What do these Freudian observations mean? It’s easy to say that anything longer than it is wide is a symbolic representation of a penis, but so what?

At the end of the day it seems like nothing more than a convoluted way to imply that certain creators are/were perverts and deviants and repel people from them without any actual sexual content to justify the allegation.

That’s definitely what Spinrad was going for, as he also indulged in another ghost of left wing intellectual analysis past in the Whipple afterward: linking fascism and homosexuality.

Fascism is for queers (and vice versa)?

Of all the old 20th century ideas left wing pundits, artists, and intellectuals are dusting off, they don’t seem eager to revisit this one for some reason, but it was definitely a thought fad for a hot few decades in the mid 20th century. Many people are at least somewhat familiar with Stalin’s regime’s recriminalization of homosexuality (Maksim Gorky once wrote “Exterminate all homosexuals and fascism will vanish” in an issue of Pravda) but few seem to realize that this line of thinking was far more spread out, including among the supposedly less authoritarian quadrants of the Marx-influenced left. Frankfurt School intellectuals Adorno and Sartre were believers, and wrote about it. For any leftist intellectual who had apprehensions about bum burgling, this was the go-to reasoning.

And Spinrad went right for it. Lord of the Swastika is full of tall, muscular blond men in skin tight leather uniforms. There are hardly any women in the book, with the most major and only named one being a train seating hostess who has a very minor role. At the end of the book, when Feric’s scientist save the human race through cloning after the gene pool is contaminated, they only clone men, suggesting that humanity will become a single sex race. Whipple points all this out and suggests the possibility that Hitler was a repressed homosexual.

Of course these elements are in the book because Spinrad put them there.

In reality, the Nazis weren’t making much heavier use of leather than other armies. Boots and a few jackets and overcoats, mostly. Even the infamous jackboots were downsized to a lace-up ankle boot later in the war to save on resources. The all black leather Nazi uniforms arose post-war in the biker and BDSM scenes. The 3rd Reich didn’t put women in combat roles and emphasized the heroism of male soldiers, but that was generally true of the British and Americans too. There were a few prominent fascist and national-socialist homosexuals, like Robert Brassillach and Ernst Rohm (ironically, Stag Stopa, the Lord of the Swastika character based on Rohm is the only named character in the book who shows any sort of heterosexuality, or sexuality period, groping a seating hostess on a train and succumbing to the wiles of Zind’s mindless mutant prostitutes) but the communist, socialist, and anarchist movements in most countries had more. At least until the commies put them all in camps or prison.

The portrayal of Nazism as some sort of hypersexualized homosexual kink fest is primarily a post war invention and once again says more about the people who created and used it than it does about the historical reality of the Nazi party. For tankies, the idea that homosexuals are natural fascists serves as a convenient excuse to purge homosexuals from the ranks without resorting to some sort of traditional moral justification, since communism rejects traditional morality. For more libertine lefties, the same spurious connection can be used to claim sexual repression is the real culprit, which in turn justifies whatever horrific extreme libertine leftists are pursuing. After all, repressing any sexual urge is impossible and will turn people into Nazis, or something.

There was also probably a much more juvenile motivation at play for all of these groups: to dissuade a certain type of lower IQ guy from admiring the Nazis by telling them that national socialism is for fags.

I’m not saying much about how The Iron Dream explores this concept, because frankly, there’s not much to say. The book keeps mentioning big strong men in tight leather, and towards the end skintight leather, and Spinrad, through Whipple, says, “This is all kinda gay, innit?” And that’s it. Fascism = gay men. Like the weapon = penis of his Freudianism he’s saying absolutely nothing new. It’s just there and it’s pointed out in the afterward by Whipple, so you absolutely don’t miss that it’s there.

I’ll just add on a final note that despite the author’s own assertion that Lord of the Swastika is extremely homoerotic, it’s not really. Mainly because Spinrad barely gives physical descriptions of the characters. He goes into exhaustive detail about the buildings (many of which aren’t even plot important) and uniforms, but the people are described in the vaguest terms. This may be a somewhat clever allusion to how Hitler's painting of buildings and landscapes are known for being better than his portraits, as well as how he helped design the infamous 3rd Reich uniforms, but combined with how one-dimensional the characters are in terms of personality, it makes any sort of actual sexual energy pretty much impossible. I’ll leave it to you to decide if that’s a good or bad thing.

History, Alternate and Not

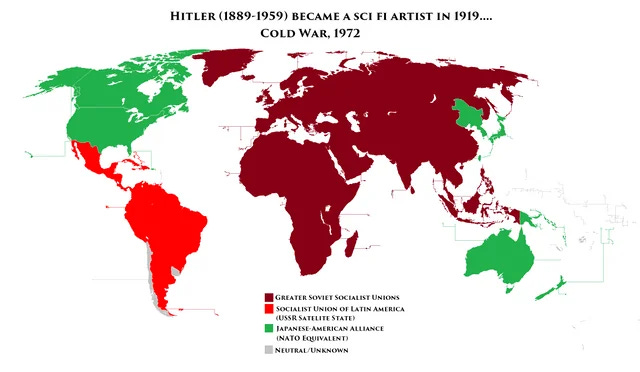

Most of the information about The Iron Dream’s alt-history world is given in the afterward. The gist of it is that the Soviet Union has now taken over most of the world, with the Empire of Japan and the USA as the only major opposition.

The full details of how this happened aren’t given, but what IS written suggests that without Hitler Germany became communist, the USSR steamrolled all of Europe fairly quickly, followed by everywhere else.

There are a few fairly big problems with this assumption. Firstly, no Hitler doesn’t mean no fascism. Fascism started with Mussolini in Italy, not Hitler. Spinrad might be looking at how poorly Italy performed in World War 2 and assuming this isn’t important, but that’s severely underestimating the influence of Fascist Italy prior to the war. It was considered to be a strong, successful country that spawned many political parties in countries across western and central Europe. Which brings me to problem two…

No Hitler and no Nazi party doesn’t mean no organized anti-communist right wing, in Germany or elsewhere. The German freikorps had already crushed one major attempted communist uprising. They were well armed and trained, and not-so-secretly allied with the German military. This would be a major obstacle to any communist takeover of Germany. Outside of Germany there were groups like the Fatherland Front in Austria and the Falangists in Spain, and groups like the Rexists in Belgium, the Iron Legion in Romania, and the Arrow Cross in Hungary would likely have arisen in some slightly different form, even without the NSDAP to inspire them. All of these groups would form a formidable obstacle to communist takeover of western and central Europe. Without the radical influence of Hitler, they may also have gotten along better with the more traditional right wing in some of those countries.

And that’s not getting into Asia, Africa, and the Middle East, where despite the relative success of various communist revolutions, the regions remained stubbornly divided and independent.

For someone who decried the “Emperor of Everything” in story telling, Spinrad ironically seems to subscribe to a sort of negative version of Great Man Theory. This is a somewhat common thing I’ve noticed with leftists. Bad Man Theory. Bad Man Hitler was the only one who could partially derail Bad Man Stalin’s train global rape train (and Spinrad does make it clear that he’s no fan of the USSR).

This mindset is also on display in the supposed historical parallels of Hitler’s rise in Germany and the events of Lord of the Swastika. Spinrad once said in an interview that the economic explanations for the rise of the Nazis “never satisfied [him].” Well, in his allegory, he removed those economic explanations completely. Far from the downright dystopian levels of suicide, economic ruin, prostitution, and political street violence that consumed the Weimar Republic, the Heldon that Feric Jagger arrives to is an idyllic place where the only poverty seems to be among the Dominator controlled Universalists. In real life, the Nazi brownshirts and communist militias drew from basically the same social circles of impoverished, often unemployed young and middle-aged men. Horst Wessel even had a personal connection with his communist assassin through the same prostitute they’d both lived with at different times.

There’s also no indication that there was widespread political violence in Heldon before Feric and his Sons of the Swastika bring violence, marching in like an occupying army with their motorcycles and submachine guns. In reality the communists already tried to stage a violent coup in 1919, a year before the founding of the NSDAP and a good half a decade before they were major political players. Various friekorps groups and communist militias were already stabbing, bludgeoning, and shooting each other in the streets. The stormtroopers just took to it with particular enthusiasm.

But by erasing these complications, Spinrad is able to assert his OWN narrative. That Germany fell under the sway of Hitler, “simply on the basis of mass displays of public fetishism, orgies of blatant phallic symbolism, and mass rallies enlivened with torchlight and rabid oratory.” It’s a view of Weimar Germany and the rise of the Third Reich that’s downright insulting compared to the more complex reality, and it’s delivered with the same wink-wink, nudge-nudge “isn’t it ironic?” framing as when Spinrad has Whipple declare that the idea (((the Dominators))) represented Jews is absurd because everyone knows the Soviet Union is antisemitic (in reality, while the USSR did persecute religious Jews as part of it’s anti-religious ideology, secular Jews were actually overrepresented in important party positions).

Under the guise of fiction, Spinrad has done the common leftist thing of trying to make fascism and national socialism as senseless as possible instead of honestly trying to make sense of them. This doesn’t offer real, accurate insight, but it does reaffirm the left wing pseudo-religious view of the Nazis and Hitler as the Great Satan of all existence, an abstract representation of base desires they must reject instead of a radical movement that arose as a reaction to extreme and highly unpleasant circumstances, which has more overlap with some aspects of their own movements than they care to admit. The Iron Dream is alternate history, but it’s written in a way that deliberately misleads the reader into thinking they’re getting some sort of fundamental insight the actual history of Hitler and the Nazi Party’s rise to power, despite being so altered it’s actually nearly useless in that regard. This is a mild annoyance for those who actually know the real history, but for people who get their understanding of history from fiction and propaganda, it’s quite damaging.

The “Crypto-Fascists”: Left Wing Literati’s Enemies List

Spinrad’s paranoia that sci-fi and fantasy were full of reactionary themes wasn’t unique to him. In fact, he was decades late jumping onto the trend. Once again, I recommend JD Cowan’s The Last Fanatics: How the Genre Wars Killed Wonder if you want to get a sense of how deep that rabbit hole goes.

But Spinrad’s book did help spread that view to a wider audience by making it entertaining, and lately it’s been having a bit of a renaissance. I guess it shouldn’t be surprising in an era when the left is struggling to maintain a total lockdown on all mainstream fiction industries while filling them with preachiness, stupidity, and nepotism hires, that they would want some ammo to portray themselves as underdogs, or at least equal opponents, of an ongoing tide of fascism in fiction.

But where exactly is this tide of fascism? What are the guilty stories and what are their crimes?

Spinrad and those like him within the tradpub industry have been less forthcoming about this than you might expect, with the lone exception of Michael Moorcock. When The Iron Dream was first published, Spinrod got several major authors to provide blurbs praising the fictional Lord of the Swastika and Hitler’s writing talents. Moorcock declared that the book was comparable to the works of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, G.K. Chesterton, and Oswald Mosley. One might be inclined to think that Moorcock was just making an absurdist joke by listing those four men together, but Moorcock has accused Tolkien of being a fascist before. It seems like these authors’ Catholic conservatism was enough to create this sentiment in the self-described “anarchist feminist” Moorcock, and he took the opportunity to take another shot at them.

Moorcock was dismantled in hilarious fashion by Ursula K. LeGuin (far from a right winger herself) in her already once cited review of The Iron Dream (which really is one of the only reviews of the book worth reading), possibly completely be accident. LeGuin observed dryly (and accurately) that Lord of the Swastika has far less in common with the works of Tolkien, Lewis, and Chesterton, than Moorcock’s own work. Ubermensch type characters and stories structured around them are far more Moorcock’s purview than Tolkien’s, Lewis’s, or Chesterton’s, who tend to celebrate humble, ordinary folk, usually possessing a far more gentle compassion than Moorcock’s own protagonists.

LeGuin herself writes that The Iron Dream is taking aim at the Sword & Sorcery subgenre as a whole, and she treats the subgenre with ruthless disdain, yet she names no specific books. Maybe out of professional courtesy, but it seems like a bit of a copout. We can’t test the validity of her accusations when there’s no specific book to examine.

When LeGuin moves to the next subgenre that The Iron Dream is, in her opinion, taking aim at, the “straight SF adventure yarn,” we finally get a name. Robert Heinlein.

Heinlein, according to LeGuin, “believes in the Alpha Male, in the role of the innately (genetically) superior man, in the heroic virtues of militarism, in the desirability and necessity of authoritarian control, etc…” and “ is a very persuasive arguer for all these things.”

This is a rather reductive description of Heinlein’s views. Treating “innately” as interchangeable with “genetically” and using this to compare Heinlein to Hitler is downright dishonest, particularly considering how often Heinlein’s work goes out of its way to be non-racist and “diverse” (for lack of a better word). The protagonist of the Starship Troopers book is Filipino-American. One of the protagonists of The Moon is a Harsh Mistress is of unspecified darker skin tone, and is targeted by racists at one point because of it, to name two examples. Claiming that Heinlein believed in “the desirability and necessity of authoritarian control” is also reductive considering the numerous times in Heinlein’s work libertarian and even borderline anarchist societies are portrayed in a fairly positive light. Or we could just, you know, look at what the author himself said about his beliefs…

Whether you agree with them or not, these are Heinlein’s views, stated plainly.

Regardless, the attacks on him from the left seem to have stuck and built up. One of the top results on Google Image search for the man’s name pulls up a blog post debating the author’s problematic nature and whether he would be best brushed into the dustbin of history.

Heinlein is the only name LeGuin mentions in her review, but anyone who has been paying attention knows that there have been a plethora of other big name authors who have come under attack in the past couple decades. This recent wave of left wing media “criticism” has been different than previous forms as it’s been accompanied by a much more overt form of censorship.

Orson Scott Card was an early example, unleashing a media storm against him after making himself the face of opposition to gay marriage, to the point where years later when Ender’s Game was made into a movie, gay rights groups urged boycotting it… over a political battle they had already won (perhaps these activists understood a fundamental truth that those on the right wish to ignore: that political battles never really end). Roald Dahl had a posthumous cancellation campaign run against him a couple of years ago which resulted in his books being censored. Ian Fleming got a similar treatment. Michael Crichton has somehow escaped attention so far (probably because the zoomer prog mobs pushing this stuff don’t read his genre, as it’s too mature for their eternally-teenage minds), but the very left-leaning Dr. Seuss hasn’t. And big name writers have it easy compared to the likes of David A. Riley, who got an entire zine in trouble for publishing story over a political association he held literally half a century ago.

The constant doublethink of the “media literate” leftist crowd who are currently holding all of western culture in a death grip (in which it’s fading fast) is that all great artists have always been left wing, yet nearly every great popular story of the past must be forgotten or rewritten due to how problematic it is. This is much more extreme than left wing media critics of ages past, like Le Guin and Spinrad, but it is a natural outgrowth of their critique methods. Turning theory into a praxis of cultural control, if you will.

“When I am weaker than you I ask you for freedom because that is according to your principles; when I am stronger than you I take away your freedom because that is according to my principles.”

-Frank Herbert (an author who will come up again shortly…)

And tellingly, the previous generation has been too cowardly to do anything to reign them in. When Mercedes Lackey got banned from the Nebula Awards for using the term “colored person” instead of “person of color” in a senior moment, for example, there was no withdrawal of support for the Nebulas, just some extremely weak expressions of disapproval. The old guard has, in essence, signed off on all this by voicing no serious opposition.

I doubt the majority of members this new neon rainbow guard have read The Iron Dream, but I think a fair amount of their thought leaders (as much as “thought” can be applied to such a group) have at least skimmed it. During one Twitter argument, one of these self-appointed “media literates” accused people who don’t want 40K Space Marines retconned of wanting “every story to look like The Iron Dream.” A classic case of projection from people who want every story and author to cater to their own extremely narrow and eternally-updating demands.

A much more comprehensive rant about the need to purge the sci-fi genre of the dreaded crypto-fascists that invoked The Iron Dream directly was written by a humble commenter beneath the review of the book on the Science Fiction Ruminations vintage book blog. The review itself was another relatively forgettable rehash of the book’s afterward, but commenter “Nicoll” had a substantial list of enemies and grievances with them to share. She didn’t take too kindly to someone disagreeing with her about the quality of the Dune book series either.

As you can see (assuming you didn’t tl;dr), Nicoll took to The Iron Dream like it’s some kind of divine gospel truth. The incessant use of “failed Hitler” to describe Frank Herbert and Robert Heinlein, two of the most successful and celebrated science fiction writers of all time, is pretty amusing. May every dissident author be as “failed!”

In reality, neither man chose to pursue a political career after finding success and fame, despite Heinlein especially having ample political connections that would have served him well if he’d chosen to do so.

Frank cutting off his son Bruce is true, but, his other son Brian, who continued his father’s work, might have a different perspective on his “nightmarishly abusive” home life. For anyone who’s actually interested, his biography of his father, Dreamer of Dune, is probably a little more insightful than the irate rantings of a random internet commentator with a grudge against people she has never met.

Beyond this, many of the complaints about “problematic” themes are pretty much what you’d expect, but calling “lasbeams” baby talk is rather odd. Who would say “lasbeams” to a baby? Is any made up word “stupid baby talk” in Nicoll’s mind? If so, the fantasy and science fiction genres probably aren’t for her at all.

In general, Nicoll doesn’t seem like a fan of science fiction, even declaring it “ruined forever” because a series of popular books (and some subsequent imitators) she doesn’t like have the audacity to exist.

And therein lies the rub. “Media literates” don’t really have any love for media. What they love is their political tribe (and by extension, them) being affirmed by media. All media. Everywhere. All the time. This is why they flip-flop between claiming every popular piece of media and art is already leftist/progressive/woke and making video essays about how Disney Channel original movies are fascist. This is a contradiction but it’s not obliviousness. It’s propaganda. The point, in all cases, is the same: to expand control and sense of “ownership” of every popular franchise, production, and entertainment outlet.

This praxis is justified by the concepts that are presented in The Iron Dream, albeit by a vague and aggressive interpretation. The afterward of the book presents the fandom that has grown up around alt-Hitler’s writings in a rather sinister light, with lots of that “it can’t happen here” faux-ironic paranoia left wingers love to use where making a straight assertion might be laughed off as absurd (as the right’s straightforward assertions about communism have been). Any writer who is too out-of-step with the current left wing zeitgeist might be a “failed Hitler” who might in turn inspire more Nazis who will commit atrocities (there is zero concern for left wing atrocities of course, and any creator on the left wing side of the aisle has free-license to be as extreme, degenerate, or have as much dirty laundry, as they please).

Once again, The Iron Dream didn’t create this cultural Gulag Archipelago moment on its own, but it is part of the milieu it was born from, and continues to be referenced by some of the people involved. Not seriously taking this into account when looking at the book and its legacy would be a grave oversight.

Is The Iron Dream Worth Reading?

It depends on what you want from it, to be perfectly honest.

If you just want to be entertained, there are better ways to spend your time. The writing is clunky, the action repetitive, and the characters are one dimensional. Most of what makes the book memorable is the novelty of swastikas festooning everything and everyone wearing leather SS uniforms, which gets a lot less novel over the course of 240+ pages. It’s not the worst read ever, but that isn’t saying much.

If you’re craving some interesting alt-history to dig into, The Iron Dream is more fascinating in concept than in execution (then again, that also describes pretty much everything ever written by Harry Turtledove). There are few concrete details about the alt-history setting that alt-Hitler wrote in, with its “Greater Soviet Union” and swastika festooned cosplayers, and what we do see is overly simplistic, even lazy, showing a rather poor understanding of not just World War 2, but the events leading up to it and the Cold War as well. You also might as well just read the afterward and skip the rest if this is the part you care about, since that’s the only part where it’s really present.

Politically, The Iron Dream is a snapshot of antiquated left wing ideas about sexuality from the 1970’s that are mostly disavowed now, combined with the seeds of a cultural movement that may prove to be the most destructive movement against art that modern western civilization has ever seen.

This is where I think reading The Iron Dream has the most value. As an exercise in cultural/political anthropology. It makes a great companion piece to the twice previously mentioned The Last Fanatics, showing how the ideas and principles of the people in that book perpetuated and spread to a larger (though still niche) audience. People with this mindset (and the significantly worse zoomer cult members they’ve inspired) are as powerful a force in western society as they’ve ever been, and in this regard The Iron Dream is more culturally relevant than ever. The time when it was not only analyzed, but actively torn apart, is long past due.

If nothing else, it’s a book that will make you think, quality issues aside, and that by itself often feels like a rarity nowadays. It’s a quality more dissident writers should be striving to include in their work. There’s all too often too much of an obsession on fun, disposable escapism (which has its place, don’t get me wrong) resulting in a lack of works that leave any real lasting impact.

Spinrad and the Nazis: The Iron Dream Vindicated?

There’s just one more minor point to address. An interesting footnote, more than anything.

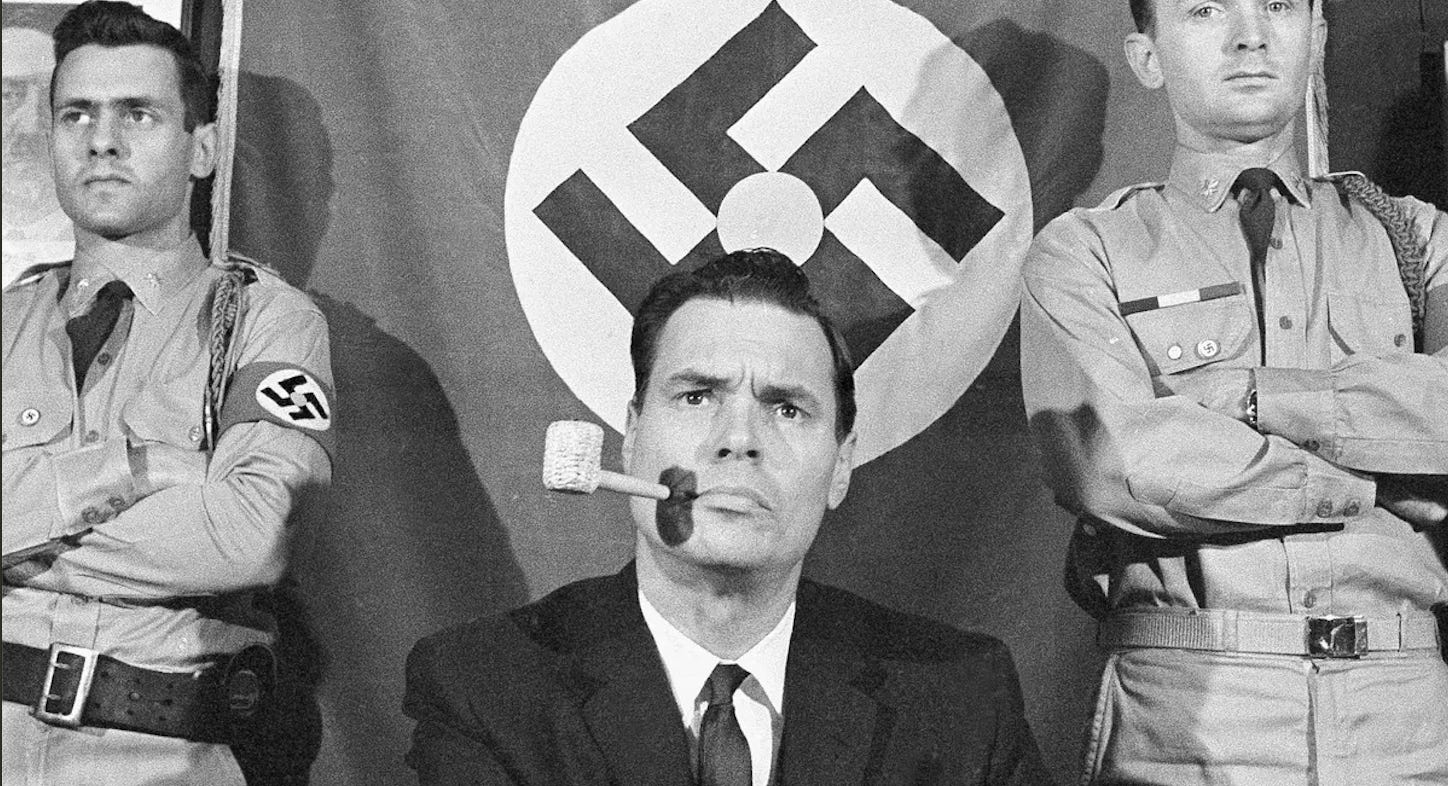

The Iron Dream has apparently made its way onto “white power literature” reading lists of actual neo-Nazis. This seems to have originated with the American Nazi Party.

The Iron Dream ended up on the party’s recommended book list that was mailed out with party literature. When Spinrad learned about this, he joked that the party must have “liked the up ending.” But was that really the reason for its inclusion? Or was something else going on? What most people don’t realize about the American Nazi Party is that most of its image was crafted, according to Rockwell’s own words (paragraph 21), to get attention through shock and outrage. Putting The Iron Dream on its reading list may have been an attempt to get attention from the science fiction fandom.

Or it may have simply been put there by a lonely science fiction fan in the party, since contrary to Spinrad’s assertions, neo-Nazi science fiction fans weren’t exactly drowning in options for reading in the genre that affirmed their beliefs in the 70’s.

I recall seeing a review on Goodreads by a user with a profile name something like “noremorse1488” (it seems to have been deleted and this was years ago, so I’m going by memory) who loved the middle part of the book, hated the afterward, and seemed unaware of the author’s views or that the book wasn’t meant to be a serious piece of “white nationalist literature.” So it’s still on those white power reading lists and some people in that fringe space are taking it completely straight, apparently.

Rockwell probably would’ve known better.

Next article: the creative art and writing of Jonathan Bowden

Thanks for this review. I'm in the minority in that I don't find the book either a powerful, terrifying warning, nor tedious. I think it's one of the funniest books I've ever read, basically because it's so much fun to watch Spinrad, a man with plenty of "issues" himself (as you've detailed beautifully) getting inside Hitler's head (as he understood it) and staying there for 200 pages.

The one point where you lost me is the link between fascism and homosexuality. The evidence will always be anecdotal, since Hitler rubbed out Röhm and put the Nazi party squarely in the anti-gay camp. (I always understood that move to be necessary as part of Hitler's agreement with the Wehrmacht to get rid of the paramilitary wing of the party, but I'm no historian.)

I'll leave gauging the Nazi-gay nexus to others, although the anecdotes are more plentiful than just Röhm. Pretty much all the prewar French fascist intellectuals were gay. At one point all but one of the postwar European Neo-Nazi party leaders were pretty obviously gay. (Jean-Marie Le Pen was the exception.) And there's the exaggerated übermensch statues of Arno Breker ... there's proto-Nazi theorist Hans Blüher. The list goes on.

I'll juts point out I've been reading arguments on this topic for decades in the conservative press. (Here's just one recent example: http://renewamerica.com/columns/fischer/121021.) Wikipedia has labeled the idea a conservative Christian conspiracy theory https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gay_Nazis_myth -- proof of where the liberal hivemind is as of today, if not previously. So I don't think you can dismiss the Nazi-gay nexus as an old leftist smear.

The Iron Dream is an eminently ambiguous novel... and you've captured this in this post.

Some reflections by me, then...

As noted The Iron Dream has something of a following among right-wingers. Kudos to Spinrad, then, for not unpublishing the novel for this. He has even put out a new edition in trade paperback format. The one I bought to have a copy of my own. Re Animus Press 2020.

The Iron Dream is a strong symbol beyond all the irony and "ways to read". Nothing can stop the archetype, not even liberal reviewers.

Heinlein, as noted, is a kind of fascist in the liberal eye. Yet Heinlein isn't anything like unpopular today. Quite the contrary.

In short, right-wing sf is heading for a new dawn.