The next writeup I had lined up was a piece about The Boondocks, which I’ve been working on, but that doesn’t feel very in-line with the holiday spirit, so I put it on hold for some unabashed positivity. Then I got dragged down with other stuff and didn’t finish in time for the holidays.

Anime is a bit of a controversial topic on the political right, whether in the dissident or mainstream sphere. There’s a sizable faction of the extremely online right that’s flat-out obsessed with it. It’s not just their aesthetic, not just the superior alternative to “woke” American media; it’s their whole lifestyle. Their vision for the future is a Moe show. On the other hand, there are people, mostly on the extreme end of the trad-right, who view it as a wicked, corrupting force. It’s true that a lot of bizarre and vile degeneracy has flourished and spread through the medium, especially through hentai and gateway “ecchi” shows, but to these people, the very style is considered to be inherently akin to child porn, regardless of what it’s being used for. They echo puritanical religious movements that banned music and dancing. Those movements never last long.

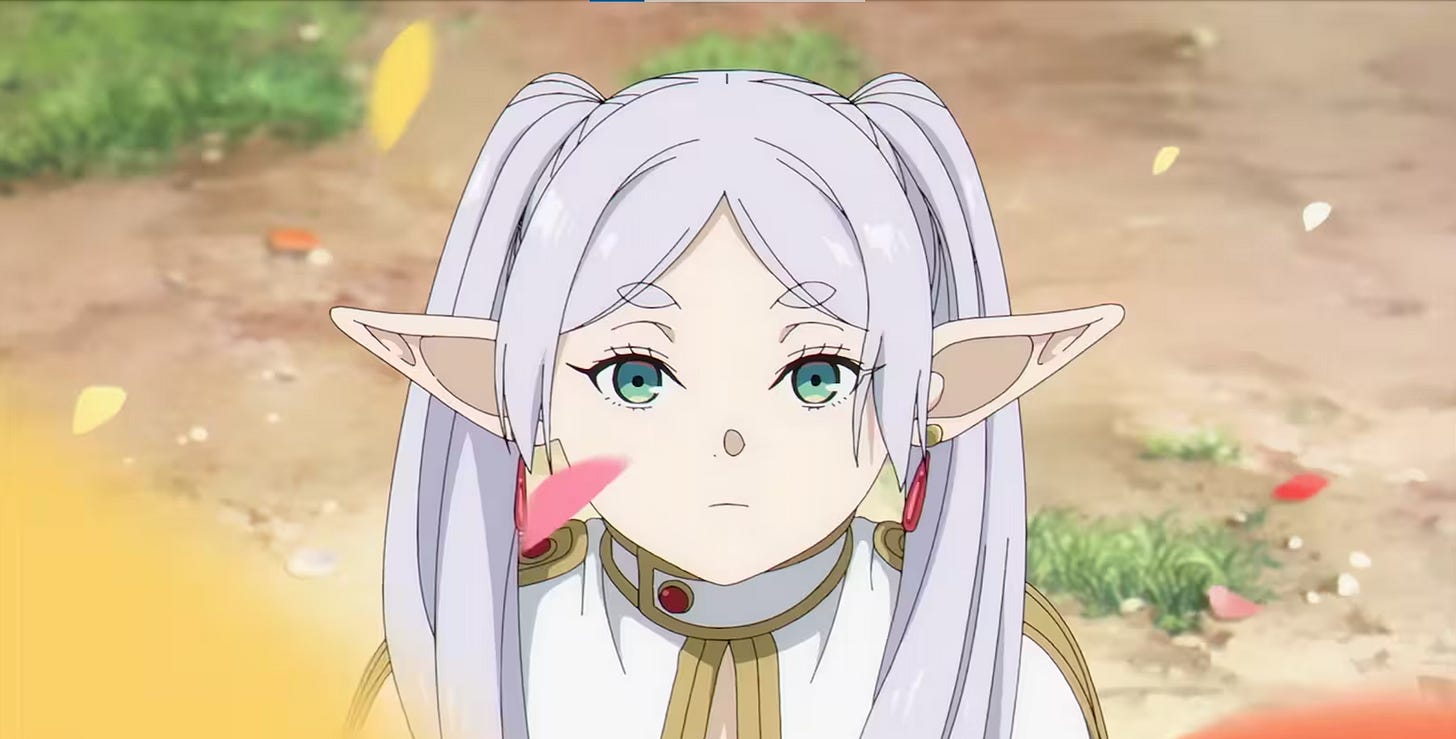

I doubt I’m going to convince anyone in the latter group to give Frieren: Beyond Journey’s End a chance, but if you’re on the fence and there’s only modern show you’re willing to give a try, make it this. Not only is it a very good show, but it’s packed with themes and lessons that are a powerful antidote to the poison of modern society. I’ve written previously about the need to include better messages in our entertainment to counter the omnipresent bad ones, and Freiren is a fantastic model for how to do this without being preachy or sacrificing story quality.

One caveat: It’s a bit on the slow side. Although there’s some good tension and action, particularly later in the season, there are a lot of quiet, still moments in Frieren, and a lot of gentle conversations. It also features virtually nothing in the way of T and A. If you have TikTok Brain, and need over-the-top stimulation every 10 seconds to hold your attention, it might not be the show for you.

The Story of Frieren

The story of Frieren begins, as its subtitle says, beyond the journey’s end. That is, after a heroic fantasy quest is over. Four heroes, Himmel, Eisen, Heiter, and Frieren, have returned from slaying the Demon King who has been terrorizing the world.

This would normally be the end of a series, or at least the end of the first arc, but here, it’s the beginning.

The story focuses on Frieren, the elf mage woman who helped slay the Demon King, as she wanders the world, visits her old friends, picks up new companions, and eventually, finds a new quest. Because Frieren is an elf, who lives for aeons, the passage of time is experienced differently by her than by a human. In just the first episode, decades are lapsed over as Frieren wanders the wilderness, doing little but solitarily studying, before returning to find her former human companions have grown old. Himmel, the optimistic, mischievous hero, dies of old age, and this is when the emotionally distant Frieren’s character arc begins, as she starts to feel regret for the time she has squandered.

And this is where the story’s brilliance lies. The idea of setting a story “after the quest’s end” isn’t a new one. What sets Frieren apart is its masterful exploration of the deep character themes of aging, death, and legacy, as well as how its exploration of these themes are used to build up and enhance the concept of classic heroism instead of cynically trying to tear it down.

Momento Mori

Momento Mori, Latin for “remember, you will die,” is an artistic aesthetic that originated with medieval Christianity. Visual features include skulls, hourglasses, the grim reaper, and dancing skeletons. The goal was to remind people of their mortality and get them thinking about the legacy they would be leaving behind when they died, as well as the state of their soul in the afterlife.

Momento Mori wasn’t popular in most protestant sects, so the Enlightenment reduced its prominence significantly, but it had a sort of exaggerated stylistic rebirth with the Goth subculture in the 1980’s. However, the Goth subculture lacked Momento Mori’s spiritual and ethical roots. Goth was a consumerist fashion culture more than anything, which is why the death of the mall due to the rise of online shopping quickly drove it to near-extinction.

If Goth was Momento Mori’s style without the substance, Frieren brings back the substance without concern for the style. The show’s nature as a European-style fantasy with medieval Germanic influence means that it’s inevitable that some “gothic” visuals creep in, but overall Frieren is very bright and colorful, with few skulls or other trappings. It’s the themes: aging, death, and legacy, heavily interwoven throughout the show, that bring the philosophy of Memento Mori to the fore.

The relentless passage of time is almost a main character unto itself in the show. Aside from the ageless Frieren, the slayers of the Demon King grow old and die, one by one. The fleeting nature of life and the things one leaves behind after death (as well as the impact they have on others) receive constant reminders. The heroes each have a legacy in the impact of the deeds they did and the people they leave behind. The elderly have wisdom of experience that the youth lack. It may seem simple, but nurtures a mindset that flies in the face of the materialistic, hedonistic, youth-obsessed, eternal “now” attitude of modern consumer culture.

Monuments to Past Virtue

Himmel is the first of the old heroes to die, but his presence continues to be felt throughout the series, through Frieren’s memories, tales passed on by people he rescued, and statues.

The treatment of the statues is interesting. Frieren is anti-iconoclast. When was the last time that sort of position received mainstream public discourse in the West? Generally when people talk about monuments it’s revolves around tearing them down. Why they were put up to begin with doesn’t even seem to be on most people’s radar.

During their adventure, Himmel frequently pushed for statues to be made in honor of their heroic acts, sometimes of all four, sometimes just him. Frieren was cynical about this, considering it a sign of Himmel’s vanity. But because of the time progression in the show, we get to see the impact these statues have on people. How they keep memories and inspiration alive. The bonds they form between people, like Frieren and an elderly townswoman. As time goes on and the older generation dies off, these monuments become the only connections to the great deeds of the past and the humanity of the people living at the time.

Physical reminders are important. Paired with rituals of commemoration, they form the roots of a common culture that brings people together, inspires cooperation, and, if done with good values, working towards a better future.

Teach Your Children Well

Although loneliness is an often-explored mood in Frieren, the elf mage doesn’t make her journey alone. She gradually picks up companions over the course of season 1.

Fern is a young girl who ended up in the care of Heiter, the priest (the equivalent of a DnD cleric, but with a bit more Catholic and less pagan influence) who went with Frieren on the quest to kill the Demon King, after she was orphaned by war. With some coaxing from Heiter, Frieren starts training her as a mage. Then Heiter, Fern’s father figure, soon passes away, leaving Frieren as Fern’s reluctant adoptive mother.

Something similar happens with Stark, who was left an orphan when monsters attacked his village, ends up mentoring under the dwarf warrior Eisen, and then falls in with Frieren and Fern after leaving Eisen due to a fight the two had.

There are a lot of parallels to parent/child relationships, along with some classic exploration of the student and mentor relationship. We’ve seen surprisingly little of that classic storytelling cornerstone in mainstream western entertainment recently. Probably because most movies, shows, and comics are being made by people who have bad or nonexistent relationships with their parents, or whose parents didn’t bother to parent them. Pair this with narratives focusing all-too-often on female characters who never need to learn anything because the universe bends to their supremacy (Captain Marvel, She-Hulk, that woman in the new Indiana Jones whose name I can’t bother to remember, etc) and it’s hardly surprising that most modern entertainment features younger characters lecturing and showing contempt for older characters instead of learning from them.

Frieren restores the wise mentor in a realistic, grounded way. The struggles of the younger generation aren’t easy, and the guidance the older generation gives them comes from years of experience. Fern and Stark aren’t coddled or told they’re perfect the way they are, and the growth they make from being pushed saves their lives later, when they’re faced with truly lethal opponents.

Speaking of which…

Evil is Manipulative

For a series with the killing of a demon king as its origin point, Frieren takes quite a while to actually give a proper explanation of what demons in this universe are. Frieren has an encounter with a demon general she sealed away decades ago near the start of the anime, but it’s a brief confrontation, with few words between her and the monstrous, cloaked figure, mostly revolving around the nature of the magic they use, before he’s blasted to kingdom come.

It’s not until about halfway through that the demons get a proper introduction. On top of it cranking up the stakes of the series, the explanation of the nature of demons introduces a host of fascinating and potent themes.

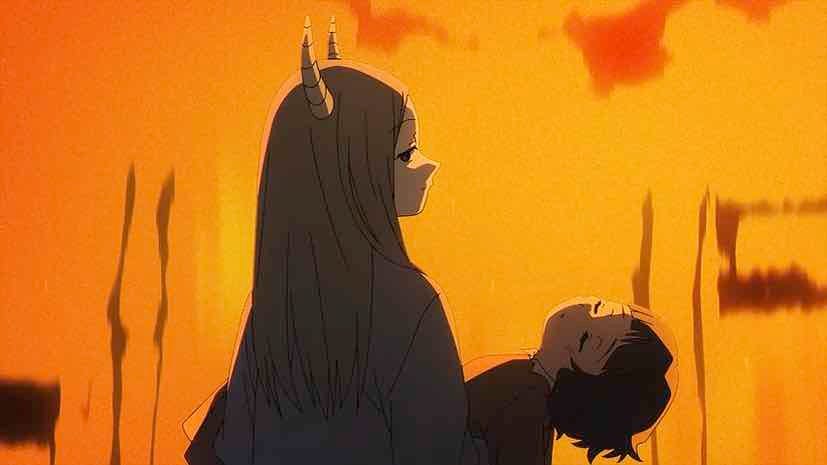

The heroes enter a town where a trio of demons are walking down the street under armed guard. Unlike the previous demon, these ones are all human looking, with fancy clothing, only their horns giving away their inhuman nature.

Frieren, with zero additional context for the situation, immediately starts charging up a spell to blast the demons. This results in her being tackled by the guards and thrown in prison for the night. The demons are there to negotiate peace between the town and the attack demon forces. As soon as Frieren hears this, she says the town is doomed.

Frieren hasn’t shown herself to be an irrational or overzealous person prior to this, so her seemingly extreme behavior in contrast to the other characters is a mystery for first time viewers. What’s the deal with demons? If they can talk they can be reasoned with, as other characters say repeatedly throughout the episode. Right?

No.

Over the course of the episode, through a mix of flashback, narration by Frieren, and views into the demons’ behavior in the present, the audience is brought to an understanding of the nature of demons and why negotiating with them is a very bad idea.

In the flashback, the four heroes who slayed the Demon King, along with an angry mob of villagers, confront a demon child (who once again looks human, but with horns) who killed and ate a girl. Once again, Frieren doesn’t hesitate, and charges up a spell to kill the demon child, but the child starts saying, “Mom” repeatedly, which gets Himmel and the villagers to stop her. The mayor is so moved by the demon child’s apparent display of humanity that he vows to take the child into his own home and raise it to be good.

Cut to an idyllic montage of the family playing with the demon girl, the mayor’s daughter making her a flower crown, etc. How adorable. Everything’s going to be just fine!

Hard cut to the mayor’s house ablaze, the mayor’s mauled body on the ground, and the demon girl standing over it all with the mayor’s unconscious daughter in her arms. There’s a very dark *Curb Your Enthusiasm theme* joke here.

This time, Himmel doesn’t hesitate. In one swift move he slices off the demon’s arms and rescues the little girl. The demon starts saying, “Mom” again, but this time no one stops Frieren from blasting it into oblivion.

Through narration Frieren tells the truth about demons. They evolved from monsters who learned to lure people to them by mimicking cries for help. Demons also abandon their children at birth, lead solitary lives, and have no concept of family. Why does the demon child say, “Mom”? Simply because the word stops humans from killing demons. “A wonderful, magical word,” as the demon child says while she lays dying.

Back in the present, we also see that the demon envoys have only come to town to figure out how to remove the town’s magic barrier so that the forces of their boss, Aura the Guillotine, can enter and slaughter the entire town. One of the demons pulls a similar trick to what the demon child in the flashback did: observing that the mayor lost a son in the war and claiming that he lost his father, which is a lie but gets the mayor to think that they might not be so different.

The message is hammered home: demons can’t be trusted or reasoned with. They use every ploy in the book to exploit people’s sympathy, just to manipulate them into letting their guard down to strike.

Just like how the most powerful and successful evil people work in real life. A society that bases standards of behavior around sympathy, “compassion” and emotionalism over logic, evidence, and the common welfare is a rich hunting ground for predators. Frieren demonstrates the potentially deadly consequences of compassion without reason. There are loads of “wonderful, magical words” that awful people can exploit to get instant sympathy and cover for their bad behavior, more being invented in the halls of academia every day. Most revolve around gender, sexuality, and race.

Which brings us to Frieren’s internet controversy, the thing that actually first brought the show to my attention…

The Great Evil Races Debate

Debates over the “issue” of fictional races of sentient beings who are pure evil have been a staple of discussions about modern fantasy for many years. Tolkien’s orcs were probably the big starting point. Frieren’s demons brought it back yet again.

These debates tend to be left wingers vs everyone else. Leftists really don’t like the concept of evil races in any medium, for a couple of reasons.

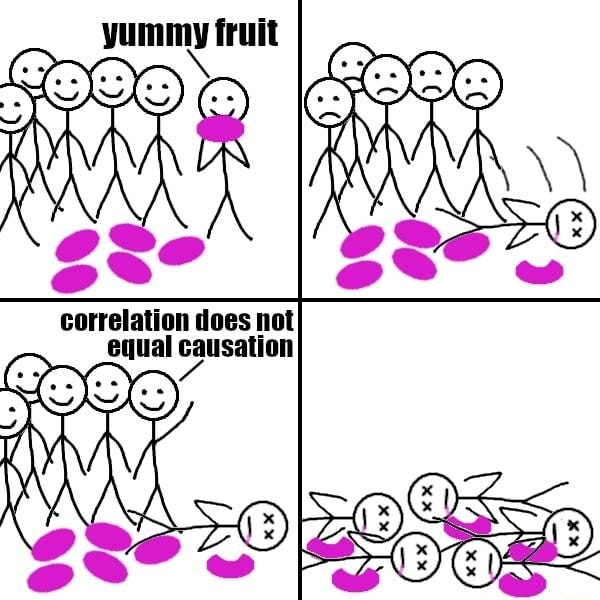

Firstly, they believe that portrayals of evil races in fiction reflects and reinforces real life racism. Most people dismiss this by pointing out orcs and demons don’t exist in real life, and have traits that no real racial group does, which are generally what make them evil. Most memes depicting hostility to evil fantasy races in a comparable way to real life races are tongue-in-cheek.

However, there are some fringe groups who take parallels they see between fictional evil races and real life races more seriously. This runs in all directions. For example, you could have someone claiming on one hand that the demons in Frieren represent (((Zionists))) and on the other hand that they represent “wypipo” (I’d say the European aesthetics of the show make the latter harder, but black supremacists frequently assert that various Europeans were actually black, so it’s not that big an obstacle). Of course, most leftists only really care about one of these things.

Furthermore, nobody developed these attitudes from interacting with these franchises in a vacuum. Anyone who sees parallels between evil fantasy races and real life races clearly already had a very negative view of those real life races. Finally, most leftists who complain about evil fantasy races either don’t care about or actively defend other fictional depictions of antisocial behavior that more directly mirror real life, like a post-apocalyptic novel about trans women murdering TERFs, so clearly their concerns about fictional works inspiring negative behavior in real life are selective and only focused on groups they like.

Another point of contention is over whether races that can’t choose to be good or evil because of an overwhelming natural inclination towards murder, rape, or other nefarious acts, can actually be labeled “evil.” This really comes down to a disagreement about moral philosophy, with the left presenting a sort of warped version of Deontology where motives determine evil, while their opponents are arguing from a more Consequentialist or Virtue Ethics position, where actions can be judged as evil in and of themselves by the effects they have. This is significant since the former tends to become a bad-faith mind reading act when applied to other people, while the later isn’t so selfishly flexible.

But that’s a topic for another time.

There’s another major theme of the demons in Frieren specifically, and the way they’re handled, that I want to address.

Experience and Enlightened Prejudice

And now for the spiciest, most “problematic” part of this analysis.

As I said, claims that a show like Frieren will cause real life racism can be dismissed by pointing out demons aren’t real and the people who equate them to real groups must have already had an extremely negative view of those groups, but there’s a deeper issue that underlies this. That issue is the very concepts of discrimination and prejudice. Because Frieren subtly and organically lays out the case that these can be good things.

In western society, discrimination and prejudice are considered two of the worst sins ever, especially by people who claim to not believe in sin. Racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, xenophobia, and all the other no-no attitudes that are regularly depicted in media as worse than murder stem from them. We have a whole system of interconnected laws to stamp out discrimination. There’s nothing western society rails against more than systemic discrimination.

But it’s all a lie. Every political and social faction discriminates. Progressives, once the standard bearers for ending discrimination in the USA, are pushing the largest scale systemic discrimination since segregation in the form of “Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion.”

While many dumber progressives will attempt to deny that this is textbook systemic discrimination, it’s openly admitted to in core “white privilege” reading. “The answer to past discrimination is current discrimination. The answer to current discrimination is future discrimination.” wrote Ibram X. Kendi in his book on the subject, admitting that this attempt to achieve equity via discrimination can only be a vicious futile cycle, possibly unintentionally.

Despite how all of this should be illegal according to the letter of Civil Rights laws, legal pushback against it has been extremely slow going, with massive institutional resistance.

On the opposite side of the coin, the group that embraced the idea of getting rid of discrimination most sincerely and personally is, ironically, boomer conservatives. And by doing so, they proved that it actually sucks. By refusing to give assistance to even their own children due to their “bootstrap” ideology, boomercons left the next generation greatly disadvantaged to more tribally minded people who funneled positions and money to their own. Boomercons (and boomers in general) left the next generation and each following one with less and less in terms of finances, culture, and identity.

These are just two of the more prominent modern examples of how the “anti-discrimination” posturing of western civilizations, and America in particular, is a lie, and fundamentally self-harming to the people who actually believe in it.

Discrimination is the action of treating people differently based on assumed traits. Prejudice is a blanket term for the attitudes and beliefs from which discrimination arises. The root from which the tree grows. Some definitions paint prejudice as being inherently irrational, and it is very often irrational, but Frieren presents a counter point. A form of prejudice that’s so well-reasoned, in situation so exaggerated, that it must be not only be acknowledged as rational, but the only moral choice.

Of all the characters, Frieren the elf is indisputably the most prejudice against demons, except for maybe the family of the little girl murdered by the demon child in the flashback. And the family is motivated by emotions. Pain and rage. Frieren isn’t. When she sees the demons in the village and immediately charges a killing spell, she’s making a calculated choice based on a thousand years of experience. Given that the other option has a near certain chance of people being gruesomely killed, anything from one person, to thousands, to the whole human race, her zero-tolerance position is the moral one. It saves lives multiple times in the show. Many lives.

In contrast to her, we have the town mayor in the flashback, who ignores what must certainly have been many lifetimes of written and oral tradition learned from harsh and bloody lessons, along with the personal lesson of a brutally murdered little girl, takes in the demon child and raises her as his own in an attempt to reform her. This costs him his own life and leaves his own daughter orphaned and homeless, but it could have been so much worse. Every single person who was in contact with the demon child when the mayor was parading her around picking flowers and the like was in mortal danger. The person he put in the greatest danger though, besides himself, was his daughter. He nearly got her killed.

This was a man taking a stand against prejudice. It was also a man taking a stand against reason and morality, even if unintentionally. The results are damning.

But in a world without demons, is this message really applicable?

Well, how about the mass psychotic delusion known as prison abolition, which is insanely popular despite using reasoning so flawed a handicapped child could drive a bus through the holes in it?

How about these?

The faces of bail reform and liberal criminal justice reform. There are many more, but that would be going off on a tangent.

No wonder we basically never see a message like Frieren’s coming from any sort of mainstream entertainment in the west anymore. The current US system has far more in common with a Batman comic where the titular hero not only allows The Joker to live but saves his life so he can continue to kill over and over again. That ain’t moral. That’s sick.

There was a time when what Frieren depicts was taken for granted, but now the exact opposite has become a sacred cow. It’s well time that sacred crow was grilled. Since western sources aren’t doing it, it’s nice that there are other avenues that are. Like media from Japan.

Religion

Some of the ways in which Frieren defies the western liberal zeitgeist are unsurprising. Japan is a country where people are still serious about law and order, it’s much more culturally homogeneous, and as a result, the people place a higher value on their cultural traditions.

But one thing about Frieren that’s a bit of an upset from the norm is its treatment of religion. Japan is highly secular, and a lot of fantasy series out of Japan present a very negative view of formalized religion. The Final Fantasy games (and many other JRPGs) frequently have some sort of angelic being as the final boss, often some representation of “God.” Anime frequently does this too. Rising of the Shield Hero, another anime I watched season 1 of that has a lot of “based” themes (for lack of a better word) features a pope-like religious leader who, spoiler alert, turns out to be a major villain. The way he didn’t open his eyes most of the time was a bit of a tip off.

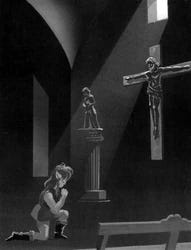

Which is why for more religious folks, Frieren will be something of a breath of fresh air. The show puts religion in a remarkably positive light for the most part, compared to the vast majority of western OR eastern TV shows.

Freiren has only really featured one religion so far, the Church of the Goddess. Aside from the obvious fact that its deity is described as female, this church is quite Christian themed. The aesthetics are Christian themed, with priests dressing similarly to Catholic priests, seeming to be expected to take some sort of vows to piety, worshippers wear icons of the Goddess in the manner of a crucifix, etc. Some devout Christians find the representation of religion being anything but a one for one depiction of Christianity to be unacceptable, but keep in mind, it was because of western guidelines that a lot of Japanese media started avoiding making direct references to real world religions.

In Frieren, the actually theology at play is only described in vague terms, but once again, it seems to be primarily a stand-in for Christianity. While Frieren herself is a doubter (starting as agnostic leaning atheist, then becoming agnostic leaning toward faith), there are several major characters who are believers, and the influence of religious faith in their lives is showed pretty universally to be a positive one.

Heiter, the “corrupt priest” of the original four heroes, is a naturally a man of vices, especially alcohol. While heavily flawed, he is constantly driven by his religious beliefs about an afterlife of reward or punishment to strive to do good. He once states that this is the reason he went on the quest with the others to slay the Demon King. Heiter clearly has natural goodness in him, but without his faith driving him, would he have risked his life on that mission, or dedicated his whole life before and afterwards to service? It’s certainly doubtful he would have done as much good as we see him do in the series.

Sein is a character who joins Frieren on her second journey who is also a priest. I don’t have much to say about him at this point, as so far he’s been essentially another version of Heiter, but even more flawed and prone to vice. Fern and Himmel are both presented as believers too, but the other character who has had the most time dedicated to his faith so far is a male elf named Kraft.

Kraft is a minor reoccurring character so far, an elf even older than Freiren, who was a hero of his own in the distant past, which has now been long forgotten. One episode centers almost entirely on Frieren and Kraft discussing religious belief, whether there’s an afterlife, and so on. Kraft is presented as old and wise, so his devotion carries weight, even when it isn’t easy for him to put certain things into words.

Overall, the depiction of the influence of religion on the lives of the characters is very positive in contrast to other eastern and western shows, and the characters of faith feel fleshed out and human. Yet the show never feels preachy or soapboxing. In fact, it feels far less so than an anti-religious western show like The Boys, with its heavy-handed depiction of evangelicals that seems like a jab at the now over 16 years out-of-date Bush era.

In conclusion

If you’re having trouble wrapping your head around how themes of reaction can be added to a story in way that’s so natural and subtle that most people don’t even really think about it (many left wing anime fans have also praised the show) give Frieren a look. This is how you do it. It’s also just a damn good show.

I wish you all a happy new year, and recommend doing your best to be ready for anything in 2024. It’s shaping up to be a wild ride.

The pace of Frieren is really slow, which is enjoyable and comfy for a non-fried brain, but it might be too boring for gen Z, the very demographic that might actually benefit a lot from watching it. It's a damn good anime, and your analysis was an interesting read.

I didn't plan to watch this show, but you've convinced me, this was an awesome review! Nice work! I'll have to do up my own review of it down the road.