A Gentle Introduction to the Creative Work of Jonathan Bowden

The political provocateur was also a prolific artist, fiction writer, and film maker. In an age of derivative media mediocrity, his bizarre creations may be just what the doctor ordered.

“Once a classic early photographer like Edward Muybridge produced an interconnected series of images featuring Greco-Roman wrestlers and running horses, the world was forever changed. Fine art now had a choice- it either replicated photography badly or in a stylized way which was loyal to a tradition running from Rembrandt to Orpen or it contrived to do something else.

What it did was go inside the mind and tap all sorts of semi-conscious and unconscious ideas, fantasies, desires, and imaginative forays. The point about this art is that it is highly personal and powerful because it comes from inside.”

-the man himself

The Artpocalypse

The quote above is more relevant than it has ever been. We’re living in an age when a new “photography” is growing and evolving in front of us, a new automation of the arts on a level that makes the camera look comparatively tame. I’m talking, of course, about AI art and writing, which is really just a mashup of existing styles and content, but a mashup that’s growing increasingly sophisticated and difficult to differentiate from the real thing. With the typing of a few words and the click of a button, any pleb or dweeb can crank out an award winning piece that can fool celebrated art critics.

The online artist community has been responding to this with a mix of gatekeeping attempts (sometimes overshooting their mark), vague calls for legislation to limit AI content (by expanding copyright laws in ways that could have major, unintended consequences), and derisive, blanket comments about the quality of AI art. The last bit is particularly interesting, because aside from the usual accusation that AI can’t make hands (it has a lot of trouble with hands, but when you have infinite generations that take only a few seconds each, it’s just a numbers game to get something passable) these comments are often extremely vague. “Soulless” and “uncanny” are two favorite words of many a critic of AI art. But what do those words mean in concrete visual terms? Nothing. They could be applied to anything.

There are much more meaningful criticisms that could be leveled at AI art. Derivative is a big one. If you browse forums or online galleries dedicated to AI art, such as Nightcafe’s “explore” tab, you’ll quickly realize that practically everything can be lumped into a dozen or so “style” categories, with less than half a dozen accounting for most works, and within each category every work quickly blends together. Individual pieces of AI art simply don’t stand out or leave much impact after you’ve seen a few pieces in a certain prompt style. Animals and humans tend to have similar static poses. These issues are caused by the AI program having to pull from many sources and defaulting to whatever it has the most references for. Everything ends up looking the same.

The reason I think so many artists are reluctant to critique AI from this particular angle though, is because human artists have the exact same problem. AI art is just the end of the road for the algorithmification of the arts that social media clout chasing started. Being original is generally punished and chasing trends is generally rewarded. On top of this, most creators all pull from a few small, shallow pools of the most popular pop culture influences. Right wing weeb/lonely male circles gravitate towards detailed drawings of perfectly sculpted animesque women.

Neurotic, gender-special Tumblrites go for an aesthetically blind selection of all the worst traits of modern western cartoons, with brown skin, thick limbs, and flushed noses.

You recognize both of these styles instantly no doubt, but how often do you remember any specific piece of art done in either style? One that really stuck with you beyond a dopamine hit of momentary pleasure or disgust interchangeable with the same feeling from a million other pieces in the genre? Have any of them ever shared a message that made you think? Unlikely. The commercial art of the current age is largely devoid of thought provoking qualities.

AI art & modern popular art have many of the same issues. The “soullessness” is because they aren’t personal. They’re pandering to the broadest audience possible. They have little to say because they’re being made by a person/program with a primary reference point of other popular media in the same genre, not actual unique life experience that gives them something unique to share. An endless feedback loop. Algorithms, algorithms. Life has become algorithms for most people. It’s all incredibly shallow.

To the artist who asks if AI art programs can create something with “soul” I ask in earnest and without intending insult: can you?

Enter Bowden

Right now about half my readers are probably thinking, “What the heck does this have to do with Jonathan Bowden?” and the other half are thinking, “Who the heck is Jonathan Bowden?”

Let’s address the latter group first.

Jonathan David Anthony Bowden was a controversial right wing cultural commentator and critic who was born to a middle class family in England, where he lived until his tragically early death at the age of 49 in 2012. Bowden lost his mother at a young age as well, which had a profound effect on him, so perhaps his family line was ill-fated from the start.

A largely self-educated polymath (he dropped out of college without completing his degree), Bowden spent the 90’s trying to poke and prod the British “conservative” party into taking more proactive and controversial stances on behalf of the British people. He started the Revolutionary Conservative Caucus (complete with printed zine) and helped start Right Now! magazine, one of very few right-leaning art and culture publications of the time that was worth a damn.

In the early 2000’s Bowden recognized the Tory party as a lost cause and abandoned it. After a brief stint with the British National Party, he became politically homeless, giving speeches and publishing articles wherever he found a platform and audience willing to listen to his ideas.

Bowden distinguished himself from other right wing commentators through his heavy focus on entertainment and the arts. High art, low art, old art, new art, his fascinations ran from Punch and Judy to post-war modernist literature, to Judge Dredd.

But Bowden didn’t just comment on the artistic creations of others, he was a prolific creator as well, who left behind a large collection of paintings, drawings, stories, and even a few films. Very strange paintings, drawings, stories, and films, that are quite divisive, even among fans of Bowden’s political commentary.

This is where the first question: what does AI art and the algorithmic, social-media controlled state of human art have to do with Jonathan Bowden? gets answered.

The Bowden Pill

Bowden’s literary and artistic work stands in stark contrast to every trend that social media has created and AI art programs feed off of.

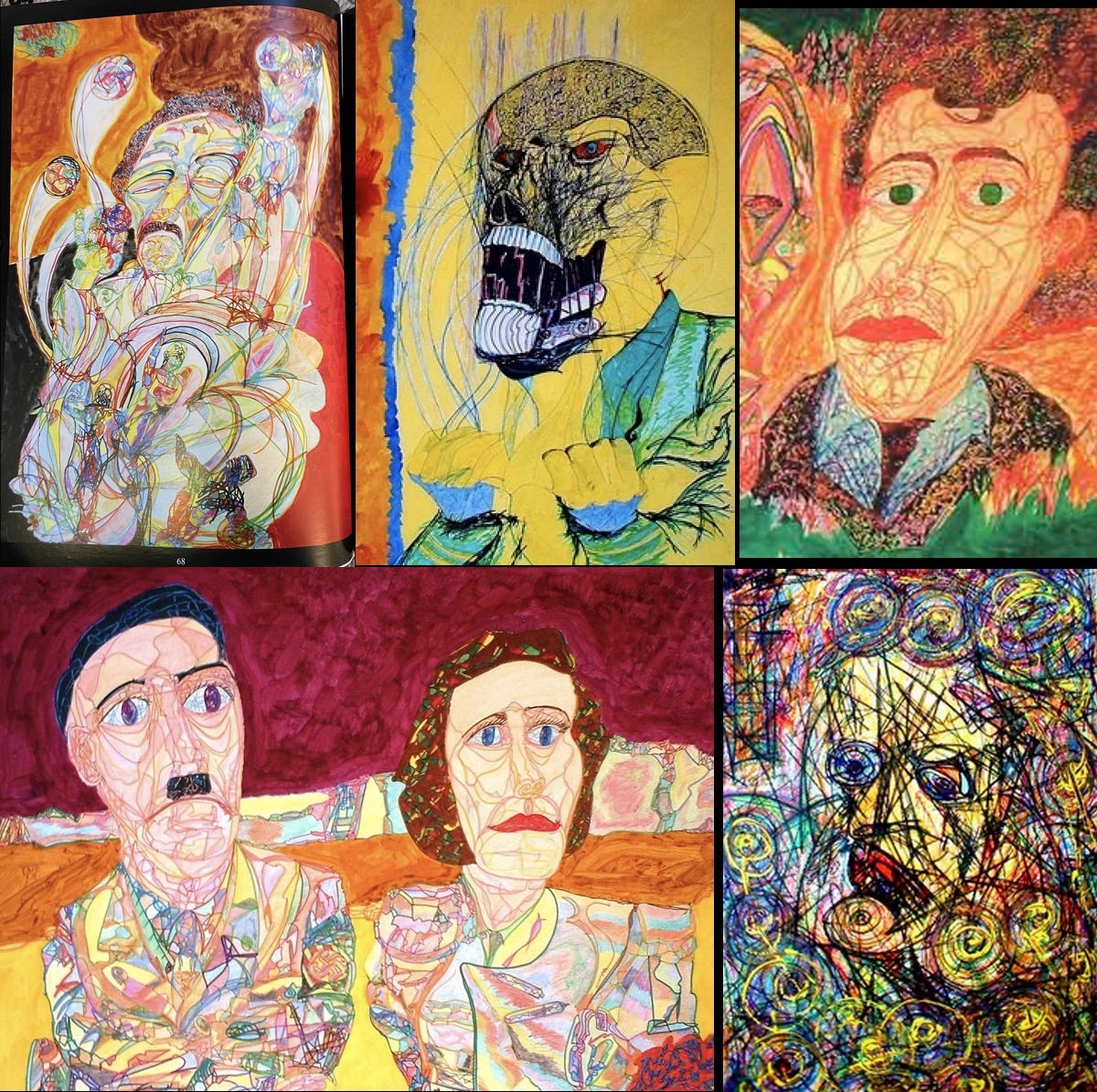

Experimental, abstract, often aesthetically ugly, with themes the man himself described as, “the demonic, strength and a concern with pure power, ugliness and fury as well as erotica and shape, or purely imaginative formulations.”

Bowden also said that he occasionally did “softer material” and “more traditional” pieces, but the vast majority of his paintings are this sort of work. Leering, brutish portraits of horribly scarred faces with severed noses giving them a skull-like appearance, people with faces split by many lines in a pseudo-cubist style that makes them look both heavily scarred and like they’ve been crudely chipped out of flesh-colored stone (including a self portrait and, infamously, one of Adolf Hitler and Leni Riefenstahl), and so on. He made several hundred of these paintings.

Bowden’s writing is no less experimental, abstract, and dark. While he was constantly referencing an extremely eclectic group of artists, writers, and film makers he had a passion for, Bowden was also always pursuing the avant-garde and the personal. Making something that was uniquely his to share was the goal.

Bowden was a passionate modernist enmeshed in a culture where modernism is often loathed. On a surface level it makes sense: modernism would naturally be opposed to and opposite of traditionalism, wouldn’t it? But modernism, Bowden noted, is no longer actually modern. It’s nearly 150 years old now. We’ve already gone past post-modernism, which, with its focus on chaos and nihilism, ran out of things to say far more quickly than modernism. We’re now in the post-post-modernist era of art, or as I call it, the Algorithmic Era. And I think Bowden’s unique approach to modernism serves as an antidote to the Algorithmic Era and its final form: AI art and writing.

Bowden had the influence of technology and the issues it causes for artists on the brain when he embraced modernism, as the quote at the top of the page shows, and that created something that almost seems like it was tailored to be a protest against the Algorithmic Era.

Algorithmic art is trend chasing and seeks popularity with the maximum number of people. Bowden’s modernism is elitist and obscure. Algorithmic art is focused on immediate satisfaction, stimulating dopamine centers as quickly as possible. Bowden’s modernism is deliberately challenging and difficult to engage with. His art works, at quick glance, look ugly and amateurish, but closer inspection reveals complexity, skill, and even a strange sort of beauty in the ugliness. His writing likewise probably looks downright incomprehensible to most people on a casual reading attempt, but digging into it and extracting the story (that’s how it feels- like a mining operation) reveals coherent plots full of pathos and memorable moments.

I don’t think AI writing will be able to replicate this any time soon. It would get lost along the way and devolve into genuinely incoherent nonsense. I haven’t really been able to recapture the vibe of his art with an AI program either, although admittedly I haven’t tried as hard as a determined techbro could,

What he created isn’t for everyone. Even among those with the brain power to come to grips with it, many will lack the patience or still find the end results unappealing. But it does something that’s damn near universally lacking in the arts across the whole spectrum now: true experimentation with the medium and a unique, yet consistent voice. And in that regard, I think for creators specifically, delving into Bowden’s work could be immensely rewarding. Sprinkling lessons from here into one’s own work just might save it from algorithmic AI hell, although you’ll probably want to dilute the approach significantly if you want something mass marketable.

Bowden’s Prose

They have not understood that men are born screaming; and when they stop; they die.

-MAD

Each orb stared blankly – at once home to a new tyranny against reason.

- Kratos

HER LIPS WERE RED>HER SOCKETS VACANT>HER SKIN GREEN>HER HAIR GOLDEN>HER LIMBS LITHE>HER EAR-RINGS & CHOKE AMBER>HER BIKINI ORMOLU>HER LEGS LONG>HER VAGINA BARELY COVERED>HER LOIN CLOUT PEARLESCENT>HER CLOAK FLAMINGO>HER HEELS HIGH>HER NAILS TAPERING>HER VOICE LIKE A BELL!

-Sixty-Foot Dolls

I’ve basically already covered Bowden’s paintings in the previous section. They’re the easiest of his works to engage with because, well, you just need to look at them.

His creative writing is more demanding of time and effort than his art or films. This is true of reading in general compared to visual art, but it’s especially true for Bowden’s writing because of his… unique prose. Bowden did not write creatively the same way he wrote his nonfiction political commentary, or gave political speeches.

His stories aren’t told in a straightforward way. Each plot point is buried in paragraphs and paragraphs of descriptive prose that’s at once vivid and abstract.

He directly references an extremely eclectic host of other works in the text, from Italian Giallo films to pre-war art movements to Judge Dredd (A Ballet of Wasps makes a rather out-of-place comparison of a medieval pub to Mega City One), most of which the average reader won’t understand. Some of the visual descriptions are outright contradictory. A passage from Kratos refers to a figure wearing “a leather mask made of jade.” Is the mask made mainly of leather or jade? No further details are given. If you like to visualize the text while reading (like I do), these contradictory descriptions create an effect that’s a bit like one of those constantly shifting AI image videos, with a consistent theme but changing details. The effect was definitely deliberate on Bowden’s part: in his film Venus Flytrap, he has one character played by 4 different women who switch out from scene snippet to scene snippet with no explanation.

“All my stories are dreams,” Bowden once said, and the bizarre, sometimes contradictory descriptions do give the stories an ethereal, dreamlike quality. However, the stories being dreams (or products of an insane narrator) is only occasionally made explicit in the texts themselves, and the ones that explicitly utilize this idea work a bit better than the ones that don’t, IMO.

Some of the references aren’t directly visually linked to the events unfolding in the story at all, and are there purely to create a mood. Sometimes these will veer of into tangents that don’t seem related to anything. Why does a story about an Italian man seeking revenge pause to give a paragraph long lecture on a nihilist communist’s art magazine? Why does a story about a very old man being offered an de-aging treatment work in an aside to the audience that the abstract art movement was funded by the CIA? That’s just how Bowden rolls.

Bowden’s dialogue is, for the most part, written in the same style as his narration. Incredibly flowery, with comparisons to various obscure historical, political, and artistic figures. It definitely isn’t anything close to realistic speech. Characters’ personalities are usually not shown through their word choice but their actions and the contents of their messages. He frequently phrases narrative descriptions as rhetorical questions. Some quirks that seem weird actually serve a significant narrative purpose. The mentions of female characters’ vaginas (when they’re still partially or fully clothed) are signifiers of sexual obsession with said characters on the part of other characters, for example. Some are more mystifying. In some stories the narration will randomly break into a “Yesss” like the narrator is a mustache twirling Snidely Whiplash, for example.

His stories are split into parts, which are functionally chapters, but generally much shorter than conventional chapters. A part typically ranges from 2/3rds of a page to only a few sentences long. In some stories these parts have naming schemes, other times they’re just numbered.

The stories usually have twists near the end, which usually involves something very bad happening. They roughly fit into the fantasy, sci-fi, and horror genres, with significant overlap.

Should a reader try to look up every reference he or she is unfamiliar with? A daunting task. Personally, I only looked them up occasionally, but I have a bit more knowledge of some of this stuff than the average person. I missed the impact of a lot of lines, no doubt, but it was a compromise for reading on a busy schedule.

Even if you manage to follow them, Bowden’s stories won’t be for everyone. They’re demanding, dark, and rarely quick to get to the point. The exact opposite of the sacred escapism so many in the populist wing of the dissident sphere crave. That said, there’s nothing else quite like them, and that’s a very rare thing to say in today’s content-saturated world. Let’s buckle up and take a closer look at some individually.

A Very Incomplete Bowden Reader

Many of Bowden’s creative works were published through The Spinning Top Club, and all of the works published this way have been made available for free in PDF form on his website. This makes these the most accessible of his books, and therefore they’ll get the most focus here.

I haven’t read all Bowden’s creative works. I only started diving into his writing a couple months ago. But even the limited amount I have been reading has given me insight I wish I had when I first started.

Start with short stories, or some of his more atypical work. There’s going to be a period of adjustment. I tried to read two of Bowden’s full length novels right off when I started. I didn’t get very far. Many would have quit there. I’m glad I didn’t.

A Ballet of Wasps:

The first short story in a story collection of the same name, this is probably the best starting point for most people, not because it’s the best of his stories, but because it’s only about four pages long. A nice micro-dose to start to adjust to Bowden’s prose.

A woodsman sits in a pub in 18th century Russia and tells boasting tales to… a vampire. A full-blown Dracula type vampire, mind you. Everyone is remarkably nonchalant about this, especially the woodsman, which is his undoing. The contents of the woodsman’s tales aren’t described in even vague detail, which I think is a bit of a weakness for this one.

The vampire gets annoyed at the woodsman’s ego, and proceeds to ambush him outside, subjecting him to a bizarre fate, which I won’t spoil. It’s not typical vampire stuff.

I think this one would have actually been better with the plot expanded on significantly, but it is what it is, and because it’s his shortest tale, it’s good to start with.

You can see why a story about a vampire, a woodsman, and no wasps or ballet is called A Ballet of Wasps, right?

Kratos:

The first story, once again, in a collection of the same name, Kratos begins with the narrator, Basildon Lancaster, stumbling in a sleepy haze through the dark streets of London before collapsing in a hotel bed and having a series of troubled dreams about his wife Fervent, a low-class northern Brit named Billy O, and the beautiful woodland cottage Billy O rented to the couple.

As Basildon slips in and out of dreams, the reader keeps getting unclear glimpses that things are not well. Basildon despises Billy O. Typical British class snobbery? Or something more? Through shifting scenes the reader is left questioning if Basildon is on a harmless business trip and is simply anxious about leaving his wife behind, or is visiting his wife in an asylum after she has lost her mind, is himself an asylum patient, or if some other sinister thing is going.

Of course there’s a big twist at the end that puts the entire narration in a drastically different context.

This is possibly my favorite, which is why I listed it second. Of all of Bowden’s stories I read, this one makes the best utilization of the “it’s a dream” concept and some of the other symbolisms and references incorporated into it. The entire story takes place in a haze of ambiguity and madness that’s essential to making it work. It’s not perfect, but as a rough gem, it’s very gemmy. At 40 pages long, it’s definitely more of an investment than A Ballet of Wasps, but still quite manageable.

Sixty-Foot Dolls:

Bowden does retro pulp sci-fi! Sort of. The fourth story in the A Ballet of Wasps collection, Sixty-Foot Dolls follows two parallel story threads for most of it, something Bowden was fond of doing.

In the first thread, two doctors, Pickford and Carruthers-Smythe, offer the oldest patient at their hospital, a man named Adam, a revolutionary age-reversing treatment Pickford has been working on. But Adam isn’t interested, and things take a turn for the bizarre when the doctors dig into his files and realize that Adam is even older than he appears. He’s been an inpatient at the hospital for at least a hundred years…

In the second thread, an attractive female android named Andalusia is stalked and “murdered” via ray-gun blast by a mysterious assailant, who takes her body to revive for some unknown purpose, in a retro futuristic setting. We’re told the events in this setting are happening in Adam’s head, although whether this is a fantasy or a memory (somehow) isn’t made clear.

Of course there’s a plot twist at the end. This one I can see ticking some readers off, but it amused me. If there’s one way Bowden can be compared to RL Stine, it’s his fondness for “bad end” plot twists, some of which feel like they come out of left field. Despite that, loads of memorable visuals and plot twists make this another personal favorite of mine, which is why it’s listed third here.

MAD:

Some of Bowden’s creative writing works aren’t stories. MAD is actually an extended sort of free-form poetic philosophical musing on the nature of life and death.

I won’t go into too much detail about it, because the owner Nine-Banded Books, the publisher who reprinted the second edition, gave it a thorough review that says more and better than I could. I’ll just say that the line “Men are born screaming, and when they stop, they die” goes as hard as just about anything ever written in the English language. Also Bowden apparently wrote this when he was just 18, although it wasn’t published until years later, and someone who said he has trouble getting into Bowden’s work enjoyed MAD.

Unfortunately, the book is out of print and doesn’t have a PDF on the Bowden archive site like The Spinning Top Club books, so if you want to read this one it may be more difficult to secure.

Apocalypse TV:

Two English gentlemen, a Christian and a Pagan, both with reactionary outlooks, discuss big news stories of the day and debate ethics.

Atypical for Bowden’s stories, this one is written entirely as dialogue, and has none of the flourishes I described in the previous section. So for those who really can’t grok Bowden’s prose, this is the book for you. It’s really a sort of hybrid of his fiction and his nonfiction political writings.

Golgotha’s Centurion:

The second story in the A Ballet of Wasps collection. The brutish Frederico Gaati returns to his provincial Italian village after years of absence to learn from the elderly town gossip that his sister Suzi has become the town harlot. Gaati vows to take violent revenge on the men who have shamed his sister, and by extension, his family name.

Another one with a twist people might feel comes out of nowhere, but has a surprising thematic tie-in to the first story in the collection. Not my favorite, but has memorable elements and descriptions, like the spray of water from a character washing the blood of himself being referred to as a “steel rainbow.”

Wilderness’ Ape:

The third story in the A Ballet of Wasps collection. A mulatto girl in Haiti rejects the advances of a voodoo priest, and he retaliates by cursing her.

A rare Bowden story with no twist. Not my favorite, but has some interesting, surreal imagery, including a three armed blue voodoo spirit.

Al Qaeda Moth:

The second of the full length Bowden novels I attempted to read. Another story with two parallel threads. In this case a classic western gunslinging story involving robbers taking a hostage and a gunman riding to her rescue on one hand, and a modern echo of the same story set in the Middle East on the other. Some memorable imagery, including a gunslinger holding a six shooter at his hip morphing into a more modern gunslinger doing the same with an Uzi in the next part.

I intend to get back to this one and finish it eventually.

The Fanatical Pursuit of Purity:

The first Bowden novel I attempted. I’m just going to quote the description from Amazon:

“The Fanatical Pursuit of Purity is a Gesamtkunstwerk or attempt at a total art-work in the Wagnerian tradition. It prefigures a puppet-stage or toy-theatre within which the lead character or marionette, Phosphorous Cool, has his circumference. Into this world other dolls - Mastodon Helix, Heathcote Dervish and Warlock Splendour Thomas - nimbly trip and spin. All of this finds itself punctuated by a third dimension or alternative space.”

If you have no idea what any of that meant, I felt the same way. Then I read a few pages and… I still have no idea. Something about witches?

This was my first attempt to read one of Bowden’s creative works and it was probably the worst choice possible. But I persevered.

Venus Fly-Trap

The seventh story in the Our Name is Legion short story collection, Venus Fly-Trap is the story of Dr. Mordred who has been engaging in bizarre experiments with plants, and his rival doctor Falicia, who comes to confront him about his behavior and her intent to get him stripped of his medical license.

This one is notable because Bowden made a film adaptation of it. I intend to give a much more detailed review of both at some point in the future, so I won’t say too much about it here.

Our Name is Legion

The first story in the short story collection of the same name, a group of Puritan men chase a woman accused of being a witch.

The tone of the twist in this one is surprisingly light and silly, given the subject matter. It’s also only two pages long, so it’s another one that’s good for dipping into if you’re having trouble handling Bowden in larger doses, but this one is SO short that it’s not much of a dose.

I’ve read a bit of a couple of other short stories: Origami Bluebeard and Grimaldi’s Leo and I’m sure I’ll finish them when the mood takes me, but I think this is plenty to get people oriented to start. Of course you don’t have to take my advice or recommendations. Try reading Lilith Before Eve or Louisiana Half-Face first if you really want to explore uncharted waters. Just don’t be surprised if you’re left totally confused.

Final Points for Readers

Bowden’s fictional works aren’t perfect. Most of them were published a few years before his death or posthumously, likely after sitting on the shelf for years. It’s possible that the flurry of publishing near the end of his life was due to an instinctual, prophetic understanding that his time was short. Bowden had a mental breakdown near the very end of his life and spent time in a psychiatric ward, being released only to die of heart failure shortly afterwards. One might notice a parallel with HP Lovecraft, who was also in and out of the mental asylum before dying relatively young of health problems.

In an interview where he was asked about Mad, Bowden said that the book probably contained errors since he wrote it “straight out” when he was 18, suggesting that he didn’t give it any serious edits or rewrites in the time since. It’s quite possible that the rest of his fiction works were written similarly. Typed out in a flurry, then put on the shelf to be published all at once near the end of his life. If this is correct, it’s hardly surprising these works have some rough edges.

Well, all artistic genius has at least a touch of madness, I firmly believe, and the most valuable tales aren’t always the most polished.

Bowden’s Films

On a final note I’ll address Bowden’s filmography, although I’ll be giving it less focus than his paintings and creative writing. This article has gone long enough, and I think I’ll address his films more in a detailed review of Venus Flytrap, which he made both a short story and film version of, some time in the future.

Most of Bowden’s stories seem pretty unfilmable, yet that didn’t stop him from making films out of several of them. On a shoestring budget. This is very apparent considering that all his films star Bowden himself, if not alone with a handful of the same (mostly female) acquaintances in supporting roles, an extremely limited amount of props, set pieces, and effects, and the “home video” nature of the camera work. I guess it shouldn’t be surprising that a man who was fixated on pushing various mediums in weird directions would try his hand at film, limited resources be damned.

The results aren’t particularly good movies in a conventional sense, but they are interesting and memorable in many ways, and they do have some quality lines, shots, and plot concepts. The main enjoyment I think normies might get out of them is watching Bowden hamming it up. The man tends to go absolutely crazy in his films, whether out of a desire to entertain the audience or because he enjoyed the catharsis.

On that note, I’ll wrap things up. Lots of pundits on the mainstream right lament a dearth of right wing creatives. These people are exposing ignorance or brainwashing on their part. Right wing authors include JRR Tolkien, CS Lewis, Robert Heinlein, Frank Herbert, and Michael Crichton, all titans of their genres whose work is still widely read and influential.

That said, here’s someone who left a large body of far more obscure and esoteric work. There’s a lot here, and I’ve been getting a lot out of it. Consider giving it a try.

Next time: The Boondocks and White Nationalists: The Strange Love Story that Actually Makes Perfect Sense

Absolutely enthralled with his art style, the bewitching layers of details could occupy the eye for hours